First published in the May 2021 issue of Metal Market Magazine

While the long-term outlook for nickel is strong, uncertainties about the near-term supply-demand balance for the metal have created volatility recently.

There is still great excitement over the vast potential for new demand in batteries for electric vehicles (EVs).

There is also interest in the substantial production potential for a new combination of processes that major Chinese nickel supplier Tsingshan has developed at the company’s operations in Indonesia.

Most sources agree that both the new demand and new supply will be real but there is significant uncertainty about the timing, extent and economics of the trends for nickel. As a result, market prices for the metal have been very volatile. Market expectations of robust demand drove the price upward over the last year, but confident reports of future increases in supply from Tsingshan encouraged demand to fall back by about 20%.

Strength in stainless

Modest brownfield – and some greenfield mine and processing – expansions have been undertaken on the fundamental strength in demand for stainless steel. For all the excitement surrounding EV batteries, stainless steel remains far and away the major market for nickel, consuming as much as 70% of global production.

“The steel market for nickel has been very strong, primarily due to stainless and growth in China,” Edward Meir, senior commodity independent consultant for ED&F Man Capital Markets, said.

“The sweet spot for nickel is in stainless. Only a small portion of demand is in EV batteries, perhaps 5% or 6% today but that will grow to 10% and 25% over the next 10 years,” Meir said. “The most substantial part of the market is still down the road. Nickel got wrapped up in the whole EV-battery story with lithium, cobalt, manganese and aluminum. Then we saw the big sell off.”

All the major end-use markets for stainless steel are strong, from construction to automotive and industrial, to appliances and flatware.

“Stainless made up 70% of demand for nickel in 2020,” Meir said, “and will still be around 60% in 2025.”

By that time battery demand will still be 17% or 18% and the big demand is still 10 or 20 years down the road so there can be no firm assumption about what the recipe will be – or even if it will use nickel at all. Research on other technologies including carbon nanotubes, zinc-air batteries and advances in solid-state storage will also continue.

Variable nickel mix

The first EV batteries were lithium compounds that contained no nickel, Will Adams, head of base metals and battery research at Fastmarkets, said. One serious initial concern was ‘range anxiety’, of being limited to a confined area near charging stations.

“The pursuit of higher energy density led to new battery chemistries, mainly in various ratios of nickel, cobalt and manganese (NCM),” Adams said.

“The original NCM battery was 1 part nickel, 1 part cobalt, and 1 part manganese, NCM 1:1:1. The amount of nickel increased through a series of battery chemistries. We saw 5:2:3 NCM, then 6:2:2, and most recently 8:1:1, which is 80% nickel.”

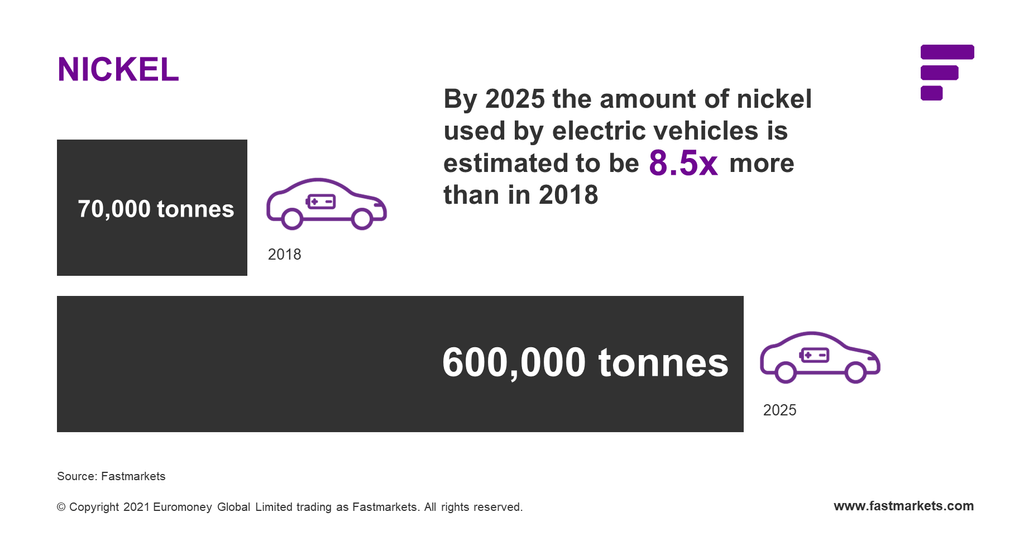

What that means in terms of nickel demand is a big number within the battery segment, but a more modest number in the context of the total global nickel market. Adams calculates roughly 45 kg of nickel per vehicle, which meant 70,000 tonnes of demand from the segment in 2018, growing to perhaps 600,000 tonnes by 2025. That is a vertiginous increase of more than 8.5 times in just seven years. Given a global annual nickel market of 2.5 million tonnes, the percentage also climbs from a sliver to a significant slice: from about 3% to 24%.

“This is going to be a big play,” Adams said, but also cautioned that neither producers nor speculators should go too far at this point.

“A couple of companies have already noted how volatile nickel and cobalt [prices] have become. Car makers could always go back to other chemistries that use less-volatile metals,” Adams said.

Adams also suggested that there may not ever be just one or two main battery-chemistry ratios.

“Several manufacturers have already said they intend to use one chemistry for standard-range vehicles and others for entry-level and high-end vehicles. There can be no assumption that 8:1:1 NCM is going to be the standard. Some makers may favor chemistries with higher manganese,” Adams said.

There is room for lots of different battery chemistries, however, Adams said.

“In most cases, nickel is likely to be a very sought-after metal. This looked like it could pose a problem as at first it was thought that only the nickel ores that went to make class-1 nickel products, such as refined metal, could be used to make the nickel sulfate that NCM lithium-ion batteries needed. But some battery raw material companies are looking at making nickel sulfate from the ores that go to make class-2 nickel material, such as nickel pig iron (NPI) – if economically viable and environmentally acceptable, then this would take some pressure off nickel producers.”

Another question on the battery market is the volume and commercial viability of recycling. Nickel and cobalt are not complicated to recycle in and of themselves, but the challenge remains to close the loop. The scrap industry for conventional internal-combustion-engine automobiles took decades to develop while the EV sector is so new that only a few of the early models are reaching the end of their service lives now.

Supply investment needed

“A year ago there was a low of $10,000 to $11,000 per tonne,” Robin Bhar, independent consultant, said. “There was a rebound close to $20,000 per tonne. There’s clearly been a rebound across all end uses, from the auto industry to aerospace. There’s definitely a better picture today than there was a year ago.”

More broadly, non-ferrous metals last had a major peak in 2010-11, Bhar said, adding that there has been under-investment since then. In nickel we’re only just getting the price range that can support reinvestment, which would be sustained levels above $20,000 per tonne.

“At present, supply is meeting demand. The balance can stay like that until about 2025. We might start to see a shortfall by then if there are not major expansion plans,” Bhar added.

Although a doubling of prices in the space of a year is a robust gain, prices now are still well below historical peaks of about $50,000 per tonne.

“That brought major investment,” Bhar said. “The market went from balance to a small surplus at the time and we have been working down the balance since then. It takes at least three or four years [from project approval to beneficial operations], so new capacity would need to be announced this year or next to be in operation by 2025.”

The base case is an orderly nickel market, Bhar said, “with normal demand development. The danger is that there is an underestimation of how quickly battery demand rises. If that accelerates beyond a certain point, it is not beyond the realm of reality for demand for nickel to go exponential. More probably we will be able to creep along with some balance.”

“Producers will continue their incremental expansions but there is only so much they can do through operational efficiency. Beyond that there will have to be prices sufficient to support greenfield development that can take five years or longer, then a mine life of 15, 20 or even 25 years,” Bhar said.

Matters of matte

In mid-April, Tsingshan, the largest global nickel producer, confirmed plans to produce nickel matte in Indonesia, derived from NPI, to partners in China that will make and sell nickel sulfate for the EV battery market.

While Tsingshan’s announcement grabbed much attention for its potential impact on the market, it is not the only producer adding nickel supply capacity. Nornickel has a two-phase plan to increase refining at its complex in Harjavalta, Finland from 65,000 tonnes per year to 100,000 tpy by 2026.

In the southern hemisphere, Panoramic Resources has reactivated its Savannah mine project in Western Australia in conjunction with an agreement with trading house Trafigura with shipments to begin by the end of the year. Mincor Resources also started operations at its Cassini mine, with the goal of commercial production next year.

“Matte technology is not new,” Andy Cole at Fastmarkets research said. “The market should have budgeted for the Tsingshan capacity in Indonesia because that has been flagged up for a while. We spotted it as far back as 2019 that Indonesia was already planning this project. The matte process is relatively easy technology and relatively simple to add to NPI. It should not be a challenge.”

“The HPAL plant is riskier,” Cole said, adding that miners generally have found HPAL technology more difficult to manage and Tsingshan has been much quieter about that than about the matte process.

“Assuming they can get the HPAL going, we’re going to have three types of nickel. It can be done on a huge scale, if the battery industry wants that. There can be a lot of nickel,” Cole said.

Reasons for caution

As sanguine as Cole seems about supply and demand, he is much less so about the speculative nature the markets have taken recently.

“The 20% sell-off in nickel prices might just be undermining the bulls. They reckon the price had just gotten to $20,000 per tonne so it could go to $22 or $25. The froth had over-inflated the price. The sell off was a measure of how frothy the market was, not how terrified the market was [of the prospects for a substantial increase in supply from Indonesia].”

“The bulls love the metals,” Cole said. “Copper has been strong, tin has been ridiculous, and now they’re chasing aluminium. Nickel rose off recent lows and they wanted in. They had their day with nickel. They hit their targets and [the announcement about matte supply from] Tsingshan made the decision for them. They booked their profits and moved on. Nickel is really just an adolescent market. It has a lot of growing to do.”

The longer-term caution for nickel bulls is that the auto markets are still deciding on battery chemistry.

“The market has been irrational but it can be much more rational. Automakers have given signs to the nickel bulls that there are other chemistries,” Cole said.

As if there were not already enough variables in the equation, one more is environmental concerns about mining in general and HPAL in particular. EV makers may increase their focus on the relative environmental impact of different metals they use in their designs, but it remains to be seen if nickel production’s position from that perspective becomes an issue or not.

Visit our hub for more in-depth insights into energy transition and its impact on commodities markets

Register for a free subscription to Metal Market Magazine here.