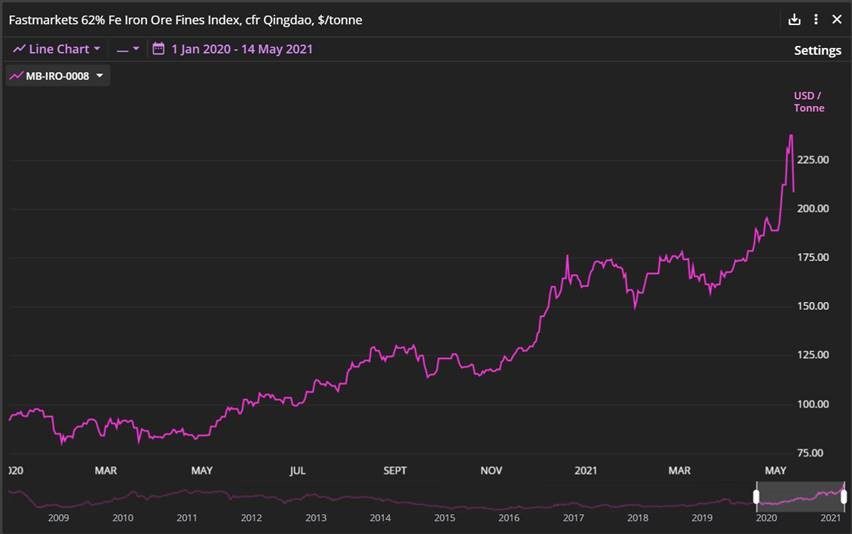

Even after this elevator ride down on May 14, the index remained comfortably above its previous 2011 highs.

How did we get here?

Of course, steel demand and iron ore supply do not change by multiple percentages over these daily timeframes. Mature markets trade as much on expectation as on current fundamentals, and changes in sentiment triggered by news and gossip can drive jarring session-to-session swings. However, panning out to a noise-reducing resolution, the explanations for iron ore’s current high price levels are very apparent.

Regular attendees to industry conferences in recent years will have repeatedly heard the major iron ore producers laying out supply plans based on anticipations of Chinese crude steel production reaching the mythical 1-billion-tonne-per-year mark by 2025 at the earliest. Not only was that level exceeded a full five years sooner in 2020, but various production issues meant that iron ore supply also undershot projections.

Following its first economic contraction in decades in the first quarter of 2020 due to the coronavirus, Beijing responded with powerful stimulus measures that saw steel demand from the construction, infrastructure and consumer goods sectors hit previously unexpected levels. Despite China’s mills producing at record rates, steel prices began climbing from around the third quarter. By May 2021, domestic prices for billet, rebar and hot-rolled coil were all posting record highs, while steelmakers were enjoying their greatest profit margins since the supply-side reform peaks of 2018.

Are price levels justified?

Floating in rarefied air some four times above the third quartile cost of production, the most tangible tether for iron ore’s price level naturally becomes the profit incentives of its consumers. Far from being squeezed by the all-time high purchasing costs, steelmakers have been chasing cargoes with a voracity reflective of the margins they can make downstream. After all, mills are convertor businesses caring more for the difference between their input costs and output prices than any absolute levels.

Some have pointed the finger for the runaway iron ore prices at the futures markets, blaming investors speculating on a macro reinflation trade. However, while there’s no denying that iron ore’s highly liquid paper contracts can impact sentiment, the hallmarks of genuine physical tightness are evident in the details.

Firstly, expanded quality differentials signal consumers’ willingness to pay up to raise productivity. The premium the 65% Fe Fines Index commands over 62% Fe hit a record level too in recent weeks and is a key bellwether of mills’ profit motive.

Secondly, higher prices for low-impurity brands bought and sold at Chinese ports compared with their seaborne traded levels (more than $50 per tonne for Vale’s Brazilian Blend) have reflected a strong appetite for immediate consumption of the most desired chemistries. You would not expect to see this kind of product-specific physical market backwardation if speculation were the main driver of the rally.

Pouring cold water

Being such an important raw material for its industrial economy, the Chinese government has unsurprisingly expressed concern over recent iron ore price levels and has tried to pour some cold water on the upsurge. But is its hosepipe pointed in the right direction?

Much of the effort to moderate price levels thus far has focused on persuading steel mills to reduce their consumption – an approach that amounts to blaming the messenger as opposed to tackling the root cause of excessive downstream demand.

The country’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) updated regulations for steelmaking capacity swaps on Thursday May 6 to ban new capacity and to increase the ratio of existing capacity that has to be retired before newer, more efficient equipment can replace it. Officials in Tangshan, the largest steel producing region, also warned mills to “maintain market order and safeguard companies’ normal operations” and vowed to look into illegal behavior including “market manipulation, spreading rumors, and hoarding.” The vagueness of these charges should give some clue as to the flexibility of what might be perceived as wrongdoing to achieve the desired outcome.

The obvious issue with focusing efforts on moderating iron ore consumption by suppressing mills’ capacity though is that it risks inflating mills’ profit margins even further if steel demand continues to exceed supply. This sort of scenario would typically see premiums for the top qualities of iron ore rise substantially, potentially offsetting any reduction in the mid-grade benchmark.

Unless that is, China’s government were to fully intervene in the market’s natural dynamic by imposing artificial controls on steel prices. Reports last week were heard of local city authorities asking steelmakers to “show stronger management and set reasonable prices on steel.” Such interference however would doubtless be counterproductive given that market prices are the most effective signals for efficient capital allocation. To reiterate, mills are the messengers in this system – the intermediaries whose rational market behavior is communicating a need for miners to invest in new supply.

High prices cure high prices

What is really needed for prices to correct to levels more reflective of marginal production costs is for either downstream steel demand to moderate or for iron ore supply to increase. While China has some specific exacerbating factors such as its highly speculative real estate sector, steel markets around the rest of the world are also fired up from post-Covid stimulus and may take some time to settle. The most plausible way this bullish trend can reverse is through supply gradually rising to rebalance demand.

Vale stated in April that it expects around 60 million tonnes of new iron ore supply to be added to the market in 2021, with itself being a major contributor of this volume. Given the margins available for anyone able to bring new supply to market at these price levels it would not be too surprising if this turns out to be a conservative estimate.

Keep an eye out for how a supply response might affect impurity penalties and grade differentials though. What was once waste will now be considered ore. Although industry majors are more limited by logistics bottlenecks than they are by geology, there will be great incentives for any players with available capacity to reduce cut-off grades to increase volumes. And while big-ticket investments like Simandou, in Guinea, may eventually bring more high-grade ore to market later in the decade, a near-term rebalancing is likely to be driven more by juniors rapidly advancing relatively low-grade short lead-time projects.

Get your copy of this whitepaper explaining market dynamics and pricing mechanisms in the high-grade iron ore segment

In this whitepaper, Fastmarkets iron ore experts Jane Fan and Peter Hannah explain the structure and dynamics of the market, with the aim of helping industry participants and outsiders alike understand more clearly the different types of products that comprise the high-grade segment, the specific factors that drive their market value and the prevailing pricing practices that influence how they are bought and sold.

Discover:

- How grade and form determine price

- The biggest producers, importers and exporters of iron ore

- The short- and long-term outlook for global iron ore markets

- And much more

[Editor’s note: This article was updated on May 19 to amend the dates mentioned in the first and second paragraphs.]